Turning a Blind Eye to Oil Spills in Venezuela

Link to article: https://stillwaterassociates.com/turning-a-blind-eye-to-oil-spills-in-venezuela/

September 28, 2020

By Barry Schaps

The preface to Former National Security Advisor Lt. General H.R. McMaster’s new book Battlegrounds, published last week, begins with “This is not the book that most people wanted me to write.” Similarly, this article is not one our audience expects to find in Stillwater’s Newsletter, but its importance to our readership requires awareness.

As Venezuela bounces from one political crisis to another, the impact on its oil industry has been profound. Measured in terms of proven crude oil reserves, experts suggest Venezuela has more oil than Saudi Arabia. Along with its political instability and corruption, the oil industry has collapsed; actual production of oil is now at a 77-year low. Production has plunged from 2.3 million barrels per day twelve years ago to less than 400,000 barrels per day in July of 2020. Contrary to the laws of supply and demand, during the period of 2003 to 2014, when oil prices were booming, PDVSA’s production started a steep decline, which no freely trading oil nation experienced.

Against this backdrop of political and economic upheaval, another oil industry catastrophe is playing out. Along the pristine white beaches of Venezuela, directly next to the Morrocoy National Park, one of the country’s most biodiverse areas, is a growing oil spill that most people haven’t seen on cable news or read about in the national media. Oddly, the August oil spill in Mauritius from the Panama-flagged, Japanese-owned iron ore ship that split on a coral reef received extensive media coverage but is less than one-third the size of the approximately 27,000-barrel Venezuelan spill. The spill in Venezuela occurred over two months ago, and reports of the oil-contaminated water first appeared on social media around August 1st. Neither the Venezuelan government nor PDVSA, the state-owned national oil company, have provided any official announcements or supervised cleanup efforts. As such, it has been difficult for experts to determine the exact cause of the spill and formulate mitigation measures.

This is not the first major spill in Venezuela and is not expected to be its last. Provea, a human-rights-focused non-governmental organization, found that from 2010 to 2016 PDVSA was responsible for 46,820 spills of crude and other contaminating substances, “with a total of 856,722.85 barrels of crude spilled” and 30,674 of those spills affecting bodies of water.

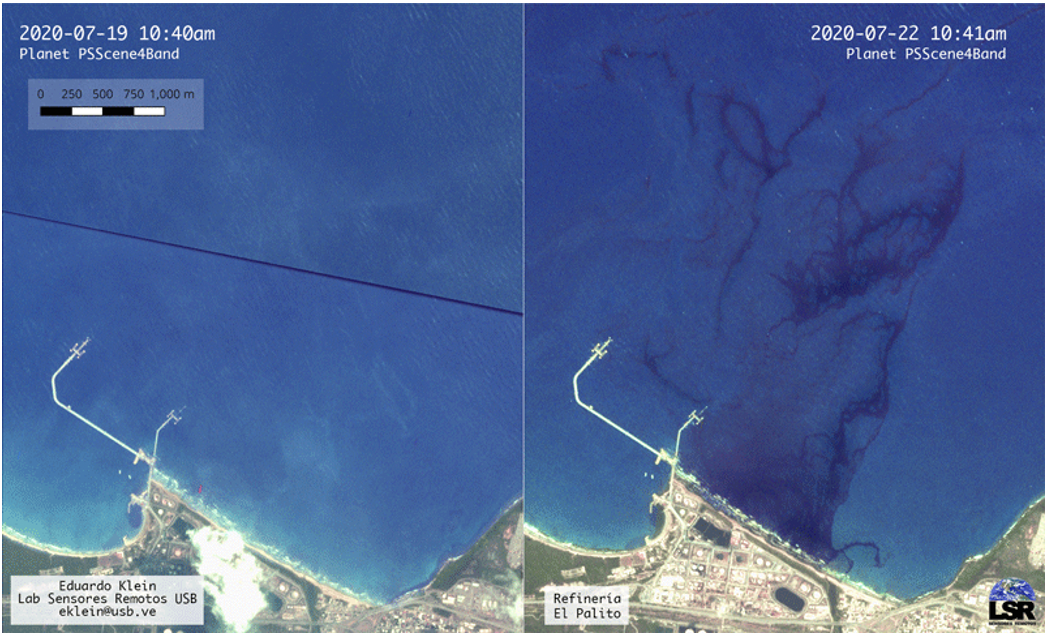

Based upon the location of the current spill in Venezuelan water, experts are focusing on two likely sources for the oil. The first location thought to be the source was a crude oil pipeline from the El Palito refinery. Satellite images, like the one below, appear to show the oil was sinking and not floating on the surface which is customary with crude oil still containing some light ends.

Satellite imagery of El Palito refinery and adjacent areas, July 19, 2020 and July 22, 2020

Based on samples gathered by local volunteers, the material appears denser than crude, so the second source it could be coming from is a refinery waste storage pit (used to collect multiple materials before reprocessing them at the refinery). The pit is close to the coast and has been known to overflow when full or after significant rains, which have occurred this summer. Whether it is coming directly from the El Palito refinery, a pipeline connected to the refinery, or a waste pit the fact of the matter is: Oil is in the water and spreading.

It is worth noting that in January of 2019 the U.S. imposed a crude oil embargo on Venezuela which does not allow Venezuelan crude oil to be processed at refineries located in the U.S. According to Reuters, since late 2019, U.S. officials have asked most of Venezuela’s fuel suppliers to avoid sending gasoline to the crisis-stricken nation. In the latest round of calls in early March between U.S. officials and oil firms, they repeated the ban, despite worsening humanitarian conditions in the country. Currently, Iran and Russia have facilitated the delivery of gasoline to the country, but the volume is not nearly enough for internal consumption. Therefore, the damaged El Palito refinery staggers towards collapse but it is the only refinery operating in the country and producing gasoline. While the embargo impacted the flow of oil into and out of Venezuela, it did not cause the political upheaval taking place nor the corruption that led up to it, and most importantly it did not create the cause of the oil spill.

Within the last three weeks, concerned environmentalists have focused their attention on a huge oil tanker (FSO Nabarima) which has been in Venezuelan waters in the Gulf of Paria for several years and is now on the verge of sinking, with 1.3 million barrels of crude aboard, because of lack of proper maintenance. If it splits apart and sinks, the resulting oil spill could be five times larger than the Exxon Valdez spill. No orders have been issued to transfer the cargo to another vessel, nor have plans been drawn up to tow the ship away to safety, if even feasible. One global body created for cases of oil spills, the International Fund for Compensation of Oil Damage (located in London), noted the vessel “does not comply with the most elementary norms of maritime safety, especially at this time that the storage of crude oil is at its maximum, which constitutes an imminent environmental risk.”

It is clear that the political, social and economic crises have now led to an environmental crisis.

Tags: oil spillCategories: News