The Renewable Fuel Standard – Part 1: A Retrospective Look

Link to article: https://stillwaterassociates.com/the-renewable-fuels-standard-part-1-a-retrospective-look/

July 1, 2018

by Brian Conroy

This is the first in a three-part series looking back at the renewable fuel standard (RFS) to reflect on the context in which it was created, what it was intended to do, how it has performed relative to the current context more than ten years later, and how the transport market should view the value of the RFS today.

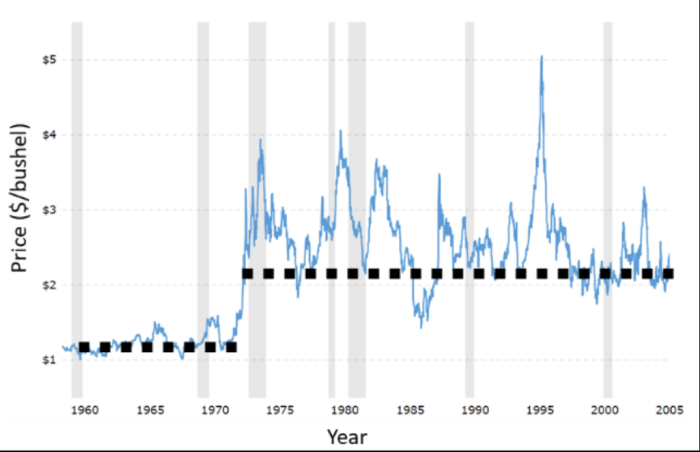

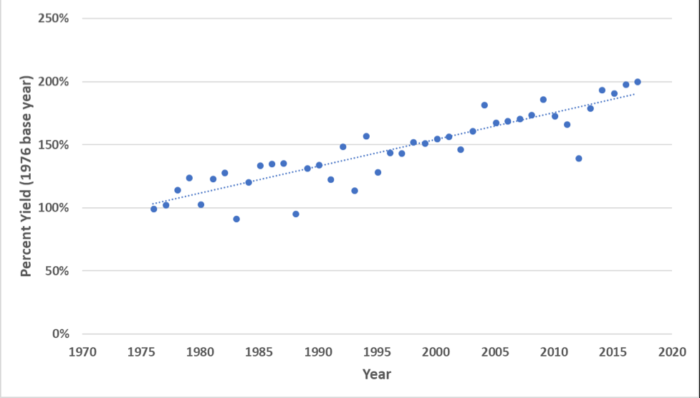

We begin our story quite a while back, so as to address historical agriculture prices and the use of corn as a metric for the overall climate in agriculture. The U.S. is very good at producing corn and improving corn yields. In fact, it has historically produced more corn than the market demanded. Prior to the 1970s, corn was priced around $1/bushel and had been there for years. Taking land out of production was not enough to raise prices, and government subsidy programs for farmers discouraged farmers from closing their farms. Then the U.S. started a policy of exporting corn to create more demand. Nearly immediately, corn prices doubled to $2/bushel, and from 1970 to 2005 prices stayed above a $2/bushel floor price. By the early 2000s, after 35 years of inflation, $2/bushel was no longer worth as much, relatively, sending numerous farms into bankruptcy and prompting the federal government to offer billions of dollars in agriculture support. In addition, new advances in corn seed technology had improved production yields such that supply was outpacing global demand for U.S. corn.

Figure 1. Corn Prices (1960-2005)

Source: Macrotrends.net

Figure 2. U.S. Corn Yield Trend

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture

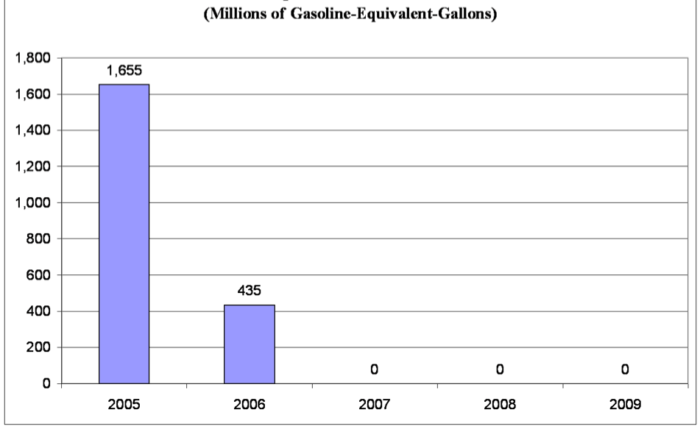

In tandem with these corn price and yield trends, methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) was found to have contaminated groundwater – rendering drinking water supplies unpalatable – and MTBE was subsequently phased out. Ethanol was a good substitute for MTBE, providing the necessary octane performance and eliminating groundwater concerns. Therefore, corn-ethanol production increased steadily as fuel suppliers demanded the MTBE substitute.

Figure 3. Estimated Consumption of MTBE as a Vehicle Fuel

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration, Estimated Consumption of Vehicle Fuels in Thousand Gasoline Equivalent Gallons, by Fuel Type, 2007 – 2011, http://www.eia.gov/renewable/afv/index.cfm.

Now, add to this scenario the effects of climate change. In the early 2000s, both Democratic and Republican lawmakers supported efforts to lower greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. As early as 2001, global oil companies such as BP started to support actions and even policies to reduce CO2 emissions from their operations and volunteered to place a self-imposed carbon price penalty on their operations to favor lower carbon investments. Other oil and gas majors followed suit.

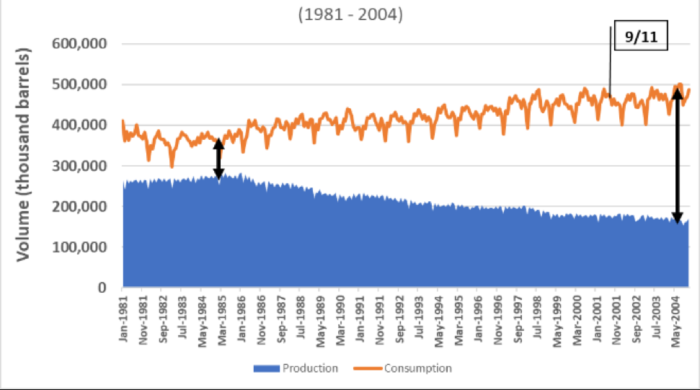

Then, on September 11, 2001, the U.S. suffered its largest-ever mainland terrorist attack. President George W. Bush was determined to secure the safety of the U.S., and military action was soon initiated in Afghanistan and Iraq. While oil demand increased, domestic oil production fell at a steady pace, heavily leveraging the stability of the U.S. economy to unfriendly nations and regions of the world.

Figure 4. U.S. Production and Consumption of Crude Oil (1981-2004)

Source: U.S. Energy Information Administration

The Republican-controlled White House and Congress asked for options, and the U.S. farming community offered more corn ethanol – a domestic-made fuel whose use would absorb excess corn production capacity.

The first version of the RFS was voted into law in 2005, and by 2007 corn ethanol producers had already exceeded the target production volumes, raising the question of whether even more biofuels could be made. The Democrat-led House of Representatives supported the production of “better biofuels” in the form of fuels with lower GHG emissions. In 2007, Congress passed a comprehensive energy bill – the Energy Independence and Security Act – which included a section updating the RFS to require a combination of higher biofuel volumes and phasing in lower GHG emissions biofuels including various types of biodiesels, cellulosic biofuels, and some imports of sugarcane ethanol.

In short, the RFS was now driven to accomplish three primary goals:

- Increase energy security

- Provide a mechanism for higher demand for U.S. agriculture

- Reduce GHG emissions from transport fuels

In September, we will publish part 2 of this series, picking up the story where we left off to discuss how the RFS has performed against each of these primary goals.

Tags: Renewable Fuel Standard, RFSCategories: Policy, White Papers