Putting the Fizz Back in the Bottle: Revenue Stream Challenges Facing Carbon Project Investors

Link to article: https://stillwaterassociates.com/putting-the-fizz-back-in-the-bottle-revenue-stream-challenges-facing-carbon-project-investors/

September 20, 2023

By Mark Rigby

Investor desire for certainty has been tested in the carbon markets in the last few years, particularly in the critical area of generating revenues to ensure project viability. Will the environment improve as carbon markets mature, or will investors and project developers be confronted with continued revenue uncertainty? While other challenges (including technology efficacy, public acceptance, and permitting) exist for developing projects focused on carbon reductions (e.g., renewable natural gas, carbon capture and storage, sustainable aviation fuel, hydrogen), this article will address the critical objective of developing project revenues. These projects involve significant capital investments and often involve long development periods to complete complex permitting requirements, new technology selection and testing, site selection, supporting utility and feedstock sourcing, and public outreach, among other activities.

Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF): Having confidence that projects will be able to attract sufficient revenues to recover these costs is critical for investors. Development of investor confidence, in turn, is necessary for programs that have created the carbon markets to achieve their objectives. While this may seem obvious, actually navigating the carbon market complexities resulting from government policies is not so straightforward. In this article, we break down these complexities and explain how investors might consider tackling the associated risks.

Many recent developments have supported the proliferation of carbon reduction projects. Passage of major federal legislation has enhanced existing programs (such as increasing the value of the federal IRS Section 45Q tax credit for carbon capture and storage (CCUS), created new programs (such as project grants designed to offset project development and capital costs) and added provisions that simplify the process for monetizing tax credits. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) continues to support the federal renewable fuel standard (RFS) through establishing annual renewable fuel volume obligations and positive policy changes. Private organizations are creating voluntary carbon programs, and several states and Canadian provinces have followed or are following California’s lead in creating low carbon fuel (LCF) and cap and trade (C&T) programs. Even so, developers and investors continue to struggle to achieve long-term, stable revenues needed to justify their capital investments.

Energy market developers and investors (who have invested in traditional and renewable power projects and on-site utility service projects such as industrial gases, steam, and water treatment) are accustomed to entering long-term agreements that provide price and sales volume certainty—upon project performance, their customers are obligated to make capacity payments. Additionally, off-take agreements have had long maturities, often with creditworthy customers. The agreements have supported significant leverage resulting in investor ability to recover their capital and return on capital over the revenue contracts’ lifetimes. Carbon market offtakes typically do not contain these commercial features.

In this article, we provide a deeper dive into the challenges with generating stable, long-term sources of value for carbon in the U.S.

Grants and Voluntary Programs

The federal government has created a broad variety of grant programs focused on all aspects of achieving national carbon reduction goals. State governments, especially California, have also developed climate-focused grant programs. Additionally, multiple corporations and foundations such as Microsoft and the Frontier coalition are establishing programs that provide project funding in a variety of forms including grants and advance purchases of carbon credits. While voluntary credit programs have grown in grant size and number of participating organizations, it remains uncertain whether such programs will be sufficient in scale and offer the pricing security to support the level of revenues required to support long-term project viability.

Grant programs do not pose the monetization issue that tax credit and environmental attribute programs raise, as discussed below, since grants are made in cash. The challenge with grant programs is investing in researching the multiplicity of programs with suitable timelines, preparing applications meeting grantor deadlines, and complying with the conditions attached to the grants. For example, U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) grant applications can take months of concentrated effort to prepare with no assurance of success.

Tax Credit Programs

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) enhanced existing tax credit programs and created new programs focused on climate change. The tax credits have defined values. For example, an investment tax credit is calculated as a defined percentage, e.g., 30%, of a qualifying investment’s capital cost. If the tax credit is a production tax credit (PTC) such as the 45Q credit (carbon sequestration), the credit has a defined value per unit of production and is escalated for inflation. The value of some credits, such as the hydrogen production credit (45V), adjusts with the project’s carbon intensity (CI) score which introduces some uncertainty. (Notably, these are the first federal programs to use CI values to determine credit value, so markets are hesitant to make commitments before the Treasury Department issues guidance on how they will implement CI calculations.) While the PTC values are well defined, the length of the timeframe for claiming the tax credits is limited. For example, the 45Q credit is limited to twelve years, creating a revenue cliff. Some projects with favorable capital and operating cost structures may be viable after twelve years, but others will require additional revenue sources. Finally, projects must be in service by certain dates to be eligible to claim the credits. While Congress has extended the in-service dates for various programs in the past, no assurance exists that extensions will occur and potential investors and lenders are reluctant to assume that such extensions will happen.

The IRA also addressed a significant issue that has historically frustrated developers’ and investors’ ability to benefit from tax credit programs. Frequently, project owners are non-taxpayers or taxpayers with minimal tax obligations. Such owners have had to execute rather complex “tax equity” transactions to realize the value of their projects’ tax credits. Fortunately, the Treasury and IRS have been responsive to comments received during the legislative process and created mechanisms to claim the benefits more easily. Some programs now include “direct pay” provisions whereby the government makes cash payments equal to the tax credit value to project owners, forestalling the need for tax equity transactions. For credits that do not qualify under the direct-pay provisions, the legislation allows a direct sale of tax credits to third parties (no partnership is needed). While the process has been simplified, market participants are still digesting how to effect transactions, helped by the issuance of IRS guidance. Unlike the direct-pay option, developers/investors will not realize the full value of the transferred tax credits, i.e., credits will be sold at a discount as buyers will require an incentive.

These new provisions do not apply to transferring other tax benefits such as tax depreciation that tax equity transactions could accomplish which may result in some parties continuing to use the more complex tax equity structures. Finally, just like grants, these programs establish conditions that must be met to claim the base value of the credits. In addition to the typical tax requirements –meeting the facility in-service date, being located within the U.S., etc. – the IRA created prevailing wage and apprenticeship provisions to qualify for the base credit value. The law also includes bonus provisions which can increase the credit value by locating projects in low-income communities and using a required amount of domestic content; each of these provisions is creating additional complexity which investors are struggling to digest as the IRS continues to develop guidance.

Environmental Attributes Programs

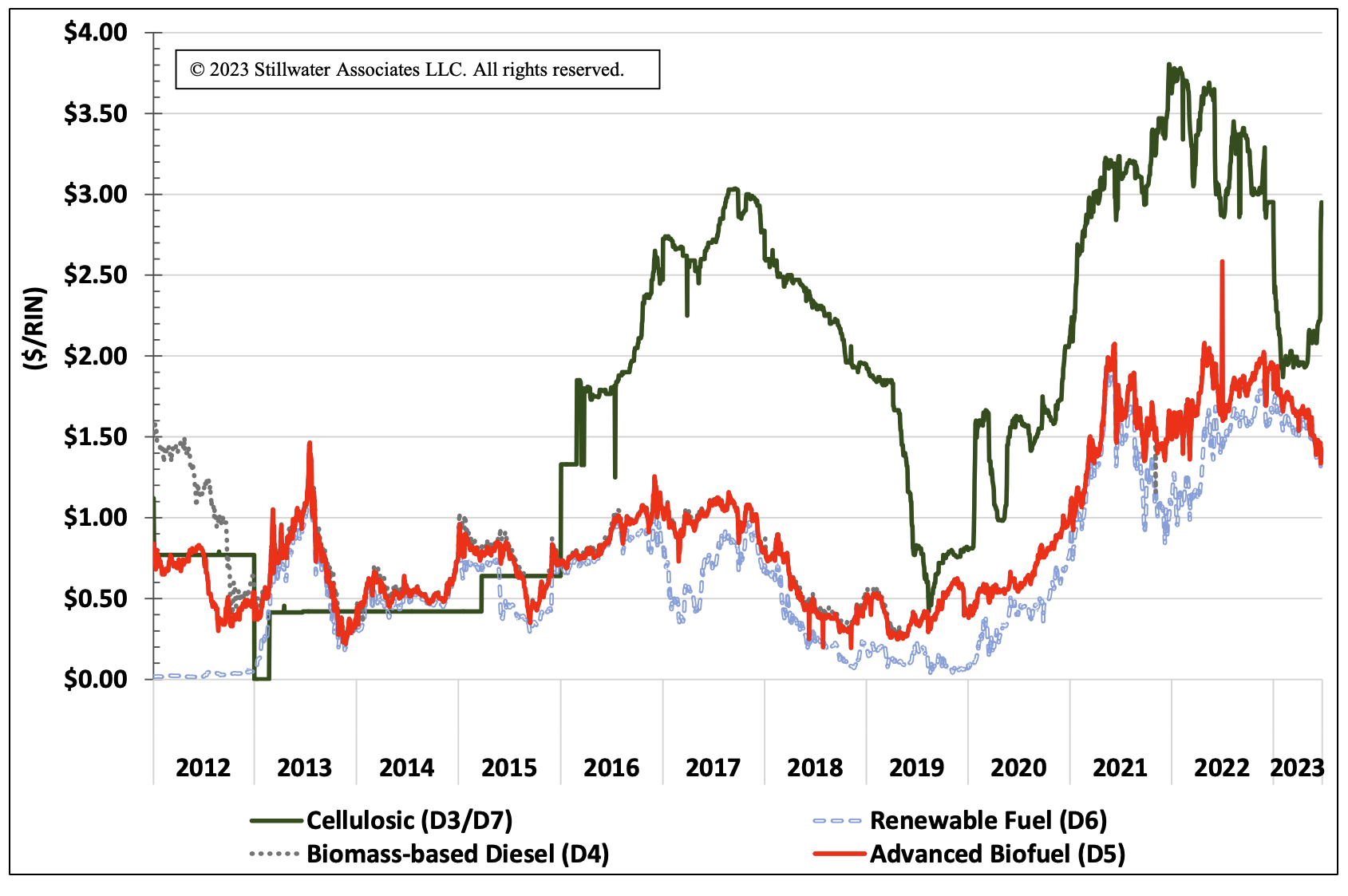

In contrast to tax credits, environmental attribute credits (such as state-level LCF programs and the federal RFS) have the advantage of longer lives than the tax credit programs (provided the underlying legislation is not amended); however, pricing of the attributes is uncertain. Legislators have selected a market-based approach for lowering carbon emissions which supports market efficiency but creates price uncertainty frustrating project investors. For example, as reported by Stillwater, California LCFS credit prices in 2022 averaged $98/MT (~45% lower than the previous year), reaching a high of $154/MT on January 6th and a low of $61/MT on November 16th. RFS credits (known as renewable identification numbers or RINs) have also shown significant volatility, as shown in the figure below.

Historic RINs Pricing (2012-2023)

Data source: OPIS

Other state and provincial programs are experiencing similar volatility. Furthermore, while California’s LCFS credit value is subject to a cap which limits project revenues, the program does not include a floor price which would provide a revenue floor. Developers and investors have suggested establishing floor values for the LCFS program, but CARB’s response to this request was that it has significant policy levers to pull in the event prices drop to levels that no longer support project development. In fact, as reported by Stillwater, CARB is expected to finalize new rules to address the low prices and other issues in 2024. While appreciated, the time required to respond to price signals through program amendments (price became an issue in 2022 while amendments won’t take effect until 2024 at the earliest) and uncertainty of the price impacts from the amendments may be problematic for developers/investors.

Hedging Environmental Attribute Prices in Financial Markets

Forward markets (both physical and financial) exist for well-established commodities such as oil, gas, and power that producers can use to hedge prices. While the maturities (most under five years) are not consistent with long-lived assets typical of energy projects, the markets have proved useful. Similar markets have not developed for environmental attributes—and they may not develop. Exchanges, such as Incubex for LCFS credits, can provide a platform for parties to conduct sales on standard terms, but forward contracts are not available. In markets which have developed successful hedging products such as power, the price being hedged is also the price of the product resulting from the activity undertaken, i.e., power. Environmental attributes such as LCFS credits generally result from activities undertaken to produce other products, therefore a direct production cost cannot be attributed to their creation. A wide variety of activities with very different cost structures – from charging an electric vehicle to removing CO2 from the atmosphere – can result in the creation of California LCFS credits.

Regulatory actions add additional price uncertainty. For example, it was possible to hedge D3 RINs under the RFS program due to certain program features and a correlation with oil prices, but a program modification terminated this hedge strategy. While financial markets may not offer hedging options, directly contracting with the parties that are required to acquire environmental attributes can be pursued as a hedging option.

Contracting Strategies for Environmental Attributes

Under the LCFS and RFS programs, the production of renewable fuels (and certain other carbon reduction activities under LCFS programs) result in the creation of the related environmental attributes by the parties that produce the renewable fuels. Obligated parties (primarily petroleum refiners, importers and blenders) are required to buy/self-generate and retire credits to comply with the programs as they sell their products, and, therefore, are a natural physical hedging counterparty for selling the attributes. While the mechanics vary, under their purchase and sale agreements, producers and obligated parties can choose which party will own the credits that result from the production of renewable fuels being sold. If the obligated party owns the credits, it can choose to use them for compliance purposes, sell the credits, or carry the credits forward into another year. (California’s LCFS program limits the ability to hold credits to obligated parties which constrains the market for sales.)

The issue for producers interested in achieving stable revenues at reasonable prices is what forward price levels can be achieved when contracting with obligated parties. Anecdotal evidence suggests that obligated parties have offered to lock in long-term prices but at steeply discounted values jeopardizing project economics. This is not surprising given historic price uncertainty and the price behavior of the end-product markets. Gasoline and diesel prices vary with the spot price of oil and the environmental attributes. If an obligated party enters a long-term contract at fixed feedstock prices (whether oil or environmental attributes) and the prices turn out to be unfavorable, the obligated party’s margins will be negatively impacted. While obligated parties may be willing to bank some low-priced credits, they will be biased against entering into long-term arrangements at prices that they perceive could decline. Producers may be better served by negotiating fixed pricing for their products and related credits (based on their project cost structures) with obligated parties at levels that provide revenue certainty but include price reopeners upon the occurrence of events that could result in significant price declines such as change in law.

Multi-Pronged Strategy

Technically, all of the benefits listed above may not be considered revenues but represent positive economic benefits. Fortunately, some programs are “stackable,” e.g., a carbon capture project may qualify for the federal 45Q tax credit and California’s LCFS program, and RNG can qualify for RINs and LCFS. Dependence on tax credits and regulatory programs which are subject to change, however, introduces “regulatory risk” into investment strategies. Market volatility increases due to regulatory risk, and markets reflect these perceived risks. The best strategy for investors who are dependent upon carbon market incentives may be to pursue multiple opportunities available in the markets, accept that projects will rarely have a single source of revenue throughout their lives, and have faith that the public sector and private organizations will continue to be supportive through extending current programs and developing new ones such as EPA’s contemplated eRINs program. Continued progress on reducing production costs to approach parity with traditional fuels may be the ultimate solution. Finally, given that current conditions are unlikely to result in the revenue certainty for which many energy investors are accustomed, investors will need to adjust their project return objectives accordingly.

About the Author

Mark Rigby comes to Stillwater with extensive experience within the energy and environmental sectors leading business development and finance functions. His experience includes assembling and managing teams to originate and execute commercial and financial arrangements for a broad variety of transactions in the North American market.

Mark has executed acquisitions and divestitures, designed and negotiated agreements to provide energy-related products and services, arranged project debt financings, structured and negotiated equity partnerships including tax equity transactions, and managed traditional finance functions (financial modeling and valuation, due diligence, risk analysis and mitigation, tax and accounting, staff recruitment and development).

Most recently, Mark has been focused on creating a new business to address climate change through developing services that will enable industrial customers to reduce their CO2 emissions, by capturing, transporting and sequestering the emissions within underground reservoirs.

Mark’s career began as a certified public accountant with KPMG followed by multiple roles with Air Products and Chemicals and DTE Energy. He holds a Master of Business Administration from The University of Virginia and a Bachelor of Science in accounting from The Pennsylvania State University.