LNG Bunkering in U.S. Ports: Change is Coming

Link to article: https://stillwaterassociates.com/lng-bunkering-in-u-s-ports-change-is-coming/

By John Wolff, Senior Associate

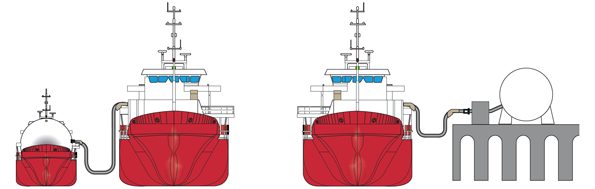

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) can be used as a fuel for ships (and trucks and buses) with specially designed fuel tanks. Currently, few U.S.- and foreign-flagged vessels are fueled with LNG, although that number may increase with the coming IMO 2020 regulation. U.S. officials have historically treated LNG with extreme caution in U.S. ports. When an LNG carrier[1] comes into Boston Harbor, for example, for deliveries to an LNG receiving terminal in the port, the United States Coast Guard (USCG) instates a safety zone around the vessel; as such, there may be no cross traffic and no outgoing channel movements while the LNG vessel is inbound. The LNG carrier is accompanied by armed USCG and police vessels. Even the interstate highway bridge under which the LNG vessel passes to reach Boston Harbor is closed in both directions and cleared while a loaded vessel is transiting. With a shifting international regulatory landscape increasing the demand for lower-sulfur and lower-emission marine fuels (including LNG), the U.S. is now indicating its intent to shift its policies and practices regarding treatment of LNG-fueled vessels at U.S. ports. Moving into the future, one could envision cruise ships with LNG bunkering operations on one side of the vessel while passengers are boarding on the other side – a significant shift from the current status quo.

Against this backdrop, on December 4, 2018, the USCG hosted its 2018 Liquefied Gas Senior Executive Forum in Houston. The program was co-sponsored by the Society of International Gas Tanker and Terminal Operators (SIGGTO) and the Society of Gas as a Marine Fuel (SGMF). The forum’s speakers addressed many aspects of using LNG as a vessel fuel. Highlights of the conference included: The USCG announcing that it will require up to 12 months to approve any LNG bunkering of a foreign-flag vessel at a U.S. port and U.S. government officials offering overviews of several policies under development and review relating to LNG permitting for bunkering operations. This article reviews the government speakers at this year’s forum, while fleet and other presenters will be covered in subsequent reviews posted here on the Stillwater Associates website.

USCG Will Require Up To 12 Months to Review Proposed LNG Bunkering Procedures

An LNG-fueled vessel can arrive at any U.S. port, although port officials exercise great caution with its arrival. Refueling a foreign-flagged LNG-fueled vessel at a U.S. port, however, is even more complex. The USCG lacks sufficient information to properly certify procedures for refueling vessels with LNG – this is particularly the case with foreign-flagged vessels about which the USCG knows less than U.S.-flagged vessels. The USCG is now seeking the appropriate path toward accommodating such LNG bunkering. As announced at the Liquefied Gas Senior Executive Forum, the USCG will require up to 12 months for consultations before specific vessels will be allowed to fuel at U.S. ports using pre-identified supply arrangements (e.g., a specific bunkering barge or truckload deliveries at a dock). The Captain of the Port, who is responsible for the controlling vessel movements, ensuring the safety and security of the port and waterways, and preventing damage to vessels and facilities, must approve any in-port LNG bunkering. With this 12-month review period, the USCG will gain a complete understanding of each vessel’s fueling systems and how the liquefied gas used to fuel vessels is delivered from source to port, ensuring proper safety measures are taken.

USCG Rear Admiral Paul Thomas, who has overall USCG responsibility in 26 states, noted at the forum that there were 2,700 gas carrier arrivals at U.S. Ports in 2017, including LNG carriers, ethane carriers, and LPG carriers. He expects conventional export business to continue to grow rapidly, while his staffing is expected to remain unchanged. Bunkering operations will contribute to that increased export activity, and U.S. policy must keep up.

Training and Regulatory Changes

The USCG is also seeking to improve officer proficiency in LNG handling through its Liquefied Gas Carrier National Center of Expertise. Thirty-five vessel inspectors took LNG vessel inspection classes through this Center of Expertise in 2018, a large number for the USCG. The USCG is also reaching out to establish industry partnerships to help with the necessary coordination.

Admiral Thomas raised the question of where inspections may be made in the future. He speculated that vessel operators may want to assure that the USCG has vetted the bunkering plan before the vessel arrives in a U.S. port. He solicited industry suggestions on having the USCG inspections overseas.

Several U.S. government speakers participated in the program’s “Regulatory Overview and Update for the Liquefied Gas Industry” panel. Todd Howard, Chief of the USCG Inspection Staff noted that many inspections are performed by authorized parties other than the USCG, and the USCG is trying to establish consistent guidelines to follow for LNG fueled vessels.

Commander Marc Montemerlo, Chief of the Hazardous Materials Division, provided a Simultaneous Operations/Vessel & Facility Reg update. He noted that the USCG is trying to get smarter on ship-to-ship LNG transfers. Considerations include the bunkering vessel, the receiving vessel (and whether a passenger vessel is taking on fuel), and guidelines from the Captain of the Port. He noted that the flag of the vessel matters. Commercial operators also spoke at the program to share their design and training approaches.

Commander Charles Bright spoke about the LNG Facility Approval Process for Safety and Security issues. He reported that the USCG is looking at updating section 33 CFR 127 (Waterfront Facilities Handling Liquefied Natural Gas and Liquefied Hazardous Gas) to update practices. The regulations’ authors did not anticipate the use of LNG as an engine fuel, instead assuming LNG would be a cargo.

Paul Roberti, the Chief Counsel for Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) at the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) noted that 49 CFR Part 193 design standards sought to have flammable gas mixes from liquefied gas spills kept on the terminal’s controlled property. These exclusion zones for large import terminals were large lots. The sites evaluated thermal radiation from pond fires, vapor dispersion and the impact of local weather conditions such as wind and rain. He noted that in 2016, Congress sought new rules for smaller LNG storage sites. The DOT will be revising 49 CFR Part 193 and will release a proposed rulemaking. He solicited ideas from the audience during his talk, noting that the comments can be included in the public record even before a rulemaking is released for comments.

There was a question regarding Transportation Worker Identification Credentials (TWIC). New rules are expected in April 2019 that will include biometrics, not just picture ID cards.

Updated U.S. DOE Review of Overall LNG Exports – Coming Soon

Amy Sweeney, the Department of Energy (DOE) Director of the Division of Natural Gas Regulation, spoke about DOE’s studies on the economic benefits of natural gas exports. In 2018, DOE released a study by National Economic Research Associates that evaluated unrestricted market-based gas export scenarios and the probability of their occurrences. Earlier studies had assumed specific volumes, such as 6 or 12 billion cubic feet per day. The preliminary study was released for comments in June and should be finalized and released soon.

Stay tuned to this space for our forthcoming reviews of the fleet presenters from this informational conference. And don’t hesitate to contact us with any questions.

—–

[1] Conventional-sized LNG carriers may carry 170,000 cubic meters (m3) of LNG while the fueling barge carriers 2,000 m3.

Tags: Bunker, bunkering, IMO 2020, IMO2020, LNG, USCGCategories: Policy