What Accounts for the Recent Surge in Cellulosic Biofuels Production?

Link to article: https://stillwaterassociates.com/what-accounts-for-the-recent-surge-in-cellulosic-biofuels-production/

May 7, 2015

by Dave Hirshfeld, MathPro Inc.

EPA has pledged to issue proposed renewable fuels volume requirements for 2014, 2015, and 2016 by June 1 and final renewable fuels volume requirements for all three years by November 30. These volume requirements set the annual Renewable Volume Obligations (RVO) for refiners and other obligated parties with respect to renewable fuels (including corn ethanol), advanced biofuels, biomass-based diesel fuel, and cellulosic biofuels (primarily cellulosic ethanol).

The late publication of these annual requirements reflect EPA’s continuing struggle to reconcile its desire to set aggressive volume obligations in hopes of calling out more advanced biofuels supply with technical and economic realities: the ethanol blendwall, the continuing low production of biomass-based diesel, and the virtual absence of cellulosic ethanol supply.

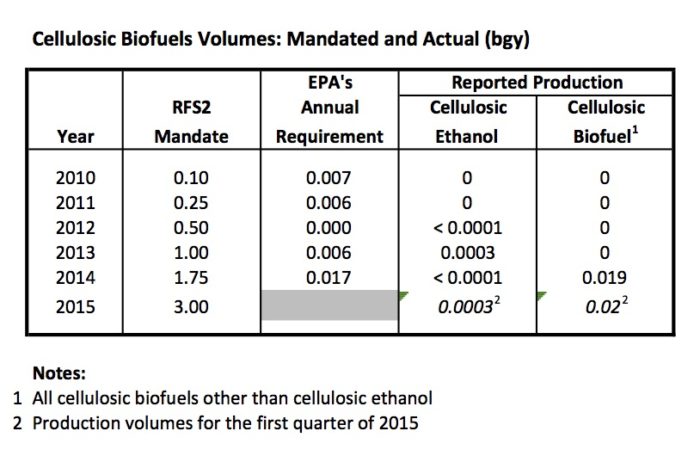

As the table indicates, the continued lack of cellulosic ethanol supply poses a vexing regulatory problem for EPA. Congress gave EPA authority to adjust the RFS2 mandate volumes if they prove unattainable in a given year. Under that authority, since 2010 EPA has set annual volume requirements for cellulosic biofuels that are far below the RFS2 mandate volumes. But each year, the annual volume requirement still has been far above the year’s annual production volume. Like good ol’ Charlie Brown, each year EPA has assumed that next year would be the one in which cellulosic biofuel production would take off.

But wait! The table suggests that 2014 may have been the year in which Lucy didn’t pull away the football. Cellulosic biofuel production moved off zero in 2014 (with most of the production coming in the fourth quarter), and the surge has continued in the first quarter of 2015.

However, the source of this surge is not first-time, commercial-scale production of cellulosic ethanol, but rather EPA’s regulatory creativity. Last July, EPA effectively expanded the definition of cellulosic biofuel to include:

- Compressed natural gas produced from biogas from landfills, municipal waste-water treatment facility digesters, agricultural digesters, and separated municipal solid waste digesters

- Liquefied natural gas produced from biogas from landfills, municipal waste-water treatment facility digesters, agricultural digesters, and separated municipal solid waste digesters

- Electricity used to power electric vehicles [and] produced from biogas from landfills, municipal waste-water treatment facility digesters, agricultural digesters, and separated municipal solid waste digesters

[EPA-420-F-14-045, July 2014]

EPA has determined that these production pathways achieve the required 60% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) compared with the fuels they displace, and therefore qualify as cellulosic biofuels (apparently, regardless of the cellulosic content of the material from which the new cellulosic biofuels are produced).

Of course, the reported volumes of biogas production are still small relative to corn ethanol or even biomass-based diesel production volumes. But EPA’s expanded definition of cellulosic biofuels has a number of benefits. These include calling out additional biofuels production, improving the optics (though not the substance) of the original RFS2 mandate for cellulosic biofuels production, increasing the number of parties (now to include biogas producers) who benefit from continuation of the RFS2 program, and – not least – increasing the pool of D3 (cellulosic biofuel) RINs available to refiners and other obligated parties in the RFS2 program.

None of this, of course, addresses the fundamental unsustainability of the RFS2 program.

Tags: White PaperCategories: Technology Development, White Papers