How to Think About Climate Change in 1500 Words

Link to article: https://stillwaterassociates.com/how-to-think-about-climate-change-in-1500-words/

June 10, 2021

by Mike Newman, Director of Parhelion Underwriting

The effects of climate change are unpredictable, leaving businesses to scramble to adapt to new risks in a shifting new normal. How should companies think about climate change?

The key characteristic of Climate Change is its unpredictability and the feeling that the natural rhythm of things has been changed. What used to be an unusually wet year is now typical. “New normal” is fleeting. Before you get used to it, it has changed again.[1] Climate science calls this Solastalgia, the distress caused by environmental change.

The most recent reports published by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) warn of a planet where Solastalgia is the norm.[2] The overriding message of the reports is that the world is not moving fast enough to avoid the harshest impacts of climate change. They project global temperatures will reach 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by the year 2040, under even the best-case emissions scenario. This temperature rise will cause an increase in extreme and unprecedented physical effects from climate change, a reality in which ever-more-ferocious cyclones and extreme droughts lead to the destruction of infrastructure and contribute to mass migration.

The Panel’s reports go on to say adaptation is now as important as prevention and that we have to learn to live with the changing reality. This means business needs to understand the new and evolving risks. Adaptation is essential, but how should we think about it?

One way for businesses to think about climate change is to look at how climate scientists think about it – they group climate risks to the economy into two categories: physical risks and transition risks.

While the physical risks from climate change (floods, heatwaves, wildfire, storms) have been discussed for many years, transition risks are a relatively new category, tied to the transformation to a low carbon economy.

Transition risk is inherent in a significant, sudden change of behavior.

Climate science groups these transition risks to the economy into market, technological, reputational, and policy and legal risks. This is a good framework to help understand the complexity of the new reality.

Climate science groups these transition risks to the economy into market, technological, reputational, and policy and legal risks. This is a good framework to help understand the complexity of the new reality.

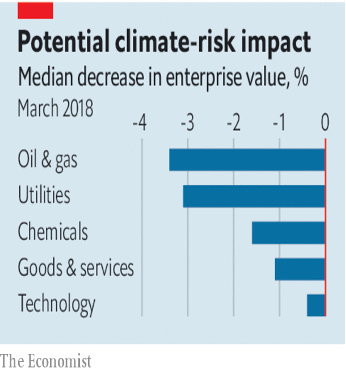

The first three risks mostly affect the parts of the economy closest to the energy transition where the transition will produce shifts in supply and demand for products and services that will create new market risks – think, waste-to renewable fuel. To the extent that new technology displaces old systems and disrupts the existing economic order, winners and losers will emerge from this reordering. Reputational risk linked to changing customer or community perceptions of a company’s contribution to the transition shapes that company’s image and the value of its brand.

Our focus, though, is on the last of these risks, policy and legal because, these will be the most common, most expensive, and the least predictable of the transitional risks.

Government policy plays an outsized part in reducing carbon emissions from carbon pricing policies (either through a tax or a market-based cap-and-trade system[3]); to standards and reporting.

In the U.S., carbon credit markets (RINs, LCFS, RGGI) underpin many of the projects contributing to the transition. Changes of law present a significant risk to these transactions.

Another goal of government policy is to require climate-related financial disclosures to the public and stakeholders. Valuable early work was done by the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)[4] that developed a set of voluntary disclosure recommendations about the climate-related financial risks and opportunities for use by companies. The TCFD framework has been the worldwide model for financial disclosure, and used by the SEC, which recently released its much-anticipated proposed rules that would require public companies to provide climate-related information in their public filings. The SEC hopes to finalize the rule by the end of 2022.

Climate liability risks are legal exposures arising from a company’s business activity and brought by people or groups against companies seen as responsible for causing or contributing to climate change. It’s the ‘who pays?’ part of climate change adaptation. That is, if future generations suffer from severe climate change, who will they hold responsible? If government policies change in line with the Paris Agreement, then two thirds of the world’s known fossil fuel reserves could not be used. If that leads to drops in the value of investments in the sector, litigation is sure to follow.

Although it is the most immediate target, the energy industry is not alone in its exposure to climate lawsuits; other sectors may face similar litigation, including construction, agriculture, automobile, coal, maritime and financial sectors.

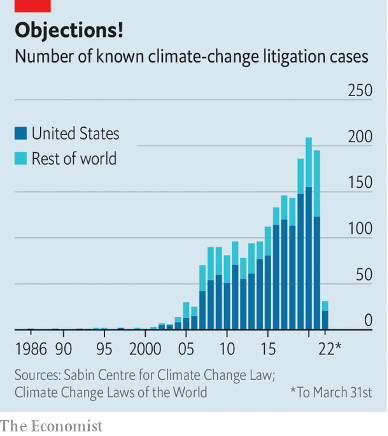

One thing is clear: Climate litigation is increasing worldwide. The number of climate change-related court cases filed globally nearly doubled between 2017 and 2020, three-quarters of which were filed in the U.S.

One thing is clear: Climate litigation is increasing worldwide. The number of climate change-related court cases filed globally nearly doubled between 2017 and 2020, three-quarters of which were filed in the U.S.

Paris brought a broader awareness of climate change and made things actionable in a way that they had not been before.

Most of the cases to date have been attempts to get governments to live up to their commitments, but lawsuits against companies associated with large emissions are multiplying. Allegations in the lawsuits vary widely. Some are based on the narrow financial interests of shareholders; some on damage done to the environment; other cases allege past misinformation, including themes from disclosure and greenwashing to fiduciary duty, consumer protection and human rights. The one element that unites climate cases is causation— a plaintiff must prove the defendant committed harmful environmental acts that had climate-related repercussions, and that the harm experienced by the plaintiff could not have happened if the events did not occur.

Still there are hurdles to filing a climate-related lawsuit. One hurdle is even if a case can be made that climate change has or will produce specific harm, finding someone to blame for them is not always easy.

Enter attribution science, a field of research that seeks to assess whether, and by how much, climate change may be responsible for extreme weather events like droughts, flooding, excessive heat or odd storm trajectories.

Climate change attribution science quantifies the influence of human-caused greenhouse gases in observed changes in natural systems. Rather than draw causal connections between emissions and events, attribution science deals in risks and probabilities: scientists have recently found, for example, that climate change increased the risk of the severe flooding in Western Europe in 2021 by at least 20 percent.

Climate attribution science should play an important role in climate litigation, central to legal debates on the causal links between human activities and global climate change.

Another problem has been agreeing on a jurisdiction. The defendant oil companies argue that cases should be heard in federal court. Plaintiffs are fighting to keep the litigation in plaintiff-friendly state courts.

No case has yet reached the merits, but the first two lawsuits are likely to go to trial in 2022. In the first, six California cities and counties have sued ExxonMobil and thirty other energy companies alleging their production and marketing of fossil fuels contributed to global warming. In the second, Mayor & City Council of Baltimore v. BP p.l.c. and other companies, Baltimore is seeking monetary damages due to sea-level rise caused by climate change and claims that fossil fuel companies knowingly contributed to climate change.

A third hurdle is that lawyers may come up against the limits of US tort law. At its strictest interpretation, climate change is too politicized, too international, too entangled in policy to litigate. As such, cases may end up in Supreme Court showdowns.

Beyond wins, losses, or settlements, the most consequential phase of climate lawsuits may be discovery, where courts require companies to turn over documents relevant to the suits, with the possibility these disclosures will reach the public. Thus, the real stakes of the litigation may not be the outcomes as much as the facts brought to light in the process.

So, how can companies protect themselves against these climate transition risks? We have three recommendations.

- Be aware of the growing body of cases as a means of identifying, assessing and mitigating liability risk. Awareness of climate change litigation outcomes can help businesses develop appropriate policy settings and proactively mitigate their exposures to climate risk.

- Put in place better data harvesting measures. This is among the most important concrete actions businesses can take now. Global disclosure standards will place greater responsibility on companies to demonstrate they are implementing risk management strategies for different climate change scenarios. This will require different quantitative and qualitative tools, data and metrics to monitor and assess exposure to physical and policy risks.

- Take a holistic approach to climate change’s transitional risks and incorporate it into procedures, enterprise risk planning, corporate governance frameworks and supply chain due diligence. Climate resilience involves organizations developing adaptive capacity to better manage risks and seize opportunities.

The process does not just expose the risks, it highlights opportunities too. More on that, next time.

[1] The Economist, March 2022

[2] https://www.conservation.org/stories/ipcc-reports-on-climate-change?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIkeSy6aKT-AIVtcLCBB3AbAFaEAMYAyAAEgLPK_D_BwE

[3] These carbon markets are now in place in, 45 national jurisdictions, and 35 subnational jurisdictions plus some U.S. states

[4] The Financial Stability Board (FSB)

Mike Newman is a risk consultant at Parhelion Underwriting, a risk finance company insuring non-traditional risks impacting investment into clean energy, climate finance and environmental commodity markets. (www.parhelionunderwriting.com).

Mike can be contacted at [email protected] or by phone at +1 (323) 459-5346.