How the Midwest bomb cyclone could impact gasoline prices throughout the U.S.

Link to article: https://stillwaterassociates.com/how-the-midwest-bomb-cyclone-could-impact-gasoline-prices-throughout-the-u-s/

April 8, 2019

By Barry Schaps

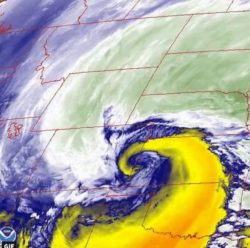

Whoever heard of a bomb cyclone weather event? In case you haven’t, here’s the rundown: A bomb cyclone is the rapid development of a “cyclonic low-pressure area” which occurs most frequently in marine environments in the winter months but can occur in continental settings and at other times of the year. Residents and farmers living in Nebraska, South Dakota, and Wisconsin learned about bomb cyclones the hard way last month when one exploded in the Midwest with devastating effects including record flooding in areas all too familiar with a flooding Missouri River (see 2011 and 1952). Past floods have been caused by seasonal melting snow further north, causing runoff and swelling rivers. This bomb, however, came with five inches of rain and 60-degree weather towards the end of winter and well before the normal spring thawing. The still-frozen ground, which held more snowpack than normal, could absorb neither the rain nor the melting snow, forcing all the water to run off the fields and drain into the local waterways feeding the massive Missouri River.

The Midwest region is characterized by large corn-growing areas with many of the nation’s largest ethanol manufacturing plants located nearby. The corn-ethanol production process has an interesting cyclical nature – corn is harvested in August and September, but ethanol production facilities operate all year. During the times when freshly harvested corn is trucked directly to the ethanol plants, the feedstock supply chain is simple, effective, and low cost. During non-harvest periods, the corn feedstock is stored in silos, in underground bins, and in piles on the ground. When the March floods came, silos were damaged by high water, underground bins were inundated with water, and ground piles were washed away, eliminating ethanol plants’ locally available corn supply.

Flood waters also impinged upon ethanol plant operations, cutting off or forcing the slowdown of manufacturing operations for several different but related reasons. Ethanol manufacturers rely heavily on rail as the means of transportation for corn as feedstock from more distant locations to the ethanol plants and for the movement of finished ethanol out of the plants. Ethanol production facilities have very limited on-site storage capacity, and their largest markets are not local but rather the heavily populated coasts which are the largest gasoline markets in the country. Midwest ethanol makes its way to these coastal markets in “unit-trains” consisting of 80 to 110 tanker rail cars. The recent flooding severely impacted rail industry infrastructure – miles of track are either completely underwater or washed away, and bridges are unstable or damaged from rushing water. Flood waters also kept thousands of tanker rail cars from making it to their intended destination for discharge. Those rail cars lucky enough to avoid the flood waters and discharge at their destinations were stranded by floodwaters or damaged and destroyed infrastructure, unable to make the journey back to their respective ethanol plants to reload. Lastly, the by-product of ethanol production – distiller’s dried grains (DDG) – is transported to market almost exclusively by rail. Approximately 80 percent of U.S.-produced DDG is fed to dairy and beef cattle with the remaining 20 percent being fed to swine and poultry.

In response to the potential logistical bottlenecks related to railroad infrastructure issues, Growth Energy (the leading U.S. biofuels trade association) sent a letter to the U.S. Transportation Secretary asking the department to “expedite rail deliveries of biofuels,” noting that “delayed transportation could impact fuel prices.” The letter under the signature of CEO Emily Skor went on to say “this situation is not being caused by a lack of ethanol production or supply at the more than 200 ethanol facilities in the U.S.,” but “the logistics problems these plants face could force plants to reduce production as their storage capacity becomes fully utilized.” She concluded by urging that all possible actions be taken to ensure critical fuel supplies are prioritized and that “delays could not only impact our industry but could ultimately increase fuels costs for American drivers.”

Eventually, the flood waters will recede, and rail transportation logistics will return to normal, but the longer-term damage to the farming industry and the overall supply/demand balance for corn will not immediately subside. When many of the levees in the farming communities broke, they released massive amounts of sand which are now covering the precious topsoil. In some areas, the sand is three feet thick, and this sand must be hauled away before the land can be put back into production. An article in Ethanol Producer Magazine highlighted the severity of this bomb cyclone: “What’s happened in a week’s time can take years to recover from. And this time is much worse than ever before. I’ve never seen anything like it in my life.”

Looking ahead, Midwest farmers who would normally plant corn from mid-April to mid-May will be unable to do so this year as the fields are too wet to support the weight of farm equipment and the soil itself is too damp for planting. As such, farmers have the choice of delaying corn planting, risking lower yields per acre when harvested, or waiting to plant soybeans instead which can be planted in early June without impacting yields resulting in a full crop. Frankly, some farmers think the entire 2019 season could be lost due to poor soil conditions and the fact that many levees need replacing or major repairs to protect fields from normal rainfall amounts.

Just this spring, numerous refinery manufacturing and reliability issues have created disruptions to gasoline supply, and crude prices have reached two-year highs, but the impact on consumer prices for gasoline at the pump will also be impacted by the havoc created for Midwest corn farmers and ethanol producers alike by the bomb cyclone.

Tags: gas prices

Categories: Wisdom from the Downstream Wizard